Originally posted on American Civil War Chronicles.

New Orleans. Monday, July 9, 1860

The schooner Clotilde, with 124 Africans on board arrived in Mobile Bay to-day. A steamboat immediately took the negroes up the river.

_____________

The short notice above, buried on page 5 of the July 11, 1860, issue of The New York Times, fails to convey the historical significance of Clotilda’s delivery of African captives into American slavery.

The importation of slaves had been illegal in the United States since January 1, 1808. The arrival of Clotilda marked the last known slave cargo delivered to the antebellum South.

Clotilda was a two-masted schooner, built and licensed in Mobile, eighty-six feet long by twenty-three feet wide. With white oak framing and planking of northern yellow pine, she had a copper-sheathed hull and measured 120 tons. Destroyed to get rid of the evidence of her illicit cargo, no known image of the Clotilda exists—a generic image of a similar ship is provided above.

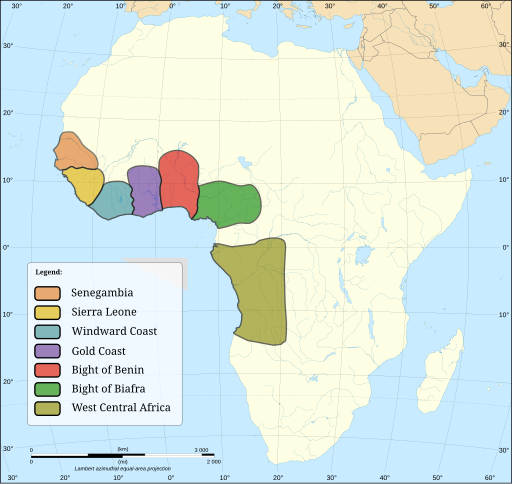

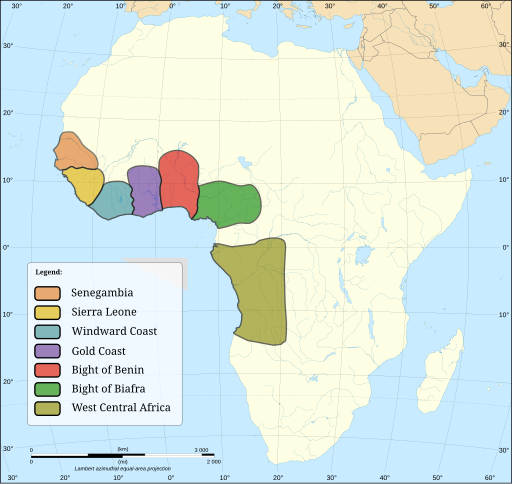

Local Alabama lore holds that wealthy Mobile shipyard owner and shipper Timothy Meaher had bet some “northern gentlemen” that he could get around the prohibition on importing slaves without being caught. Whether the bet was true or not, Meaher dispatched the sleek and swift schooner, Clotilda, to the notorious slave port of Ouidah in the Kingdom of Dahomey—now the Republic of Benin.

The Kingdom of Dahomey was a powerful military and commercial empire that dominated the slave trade on the African Slave Coast until the late 19th century. It was largely based on conquest and slave labor, international slave trading with Europeans, a centralized administration, a system of taxes, and an organized military, including units of women soldiers—called Dahomey Amazons by European observers—who fought in its wars and in slave raids. Captives taken during war and raids were enslaved for labor in the kingdom and sale to traders. The fate of many was human sacrifice.

With $9,000 in gold plus a cargo of merchandise, Captain William Foster purchased over 100 men, women and children from the Dahomey officials. They were primarily Tarkbar people taken from near Tamale, present-day Ghana. Captain Foster wrote, “from thence I went to see the King of Dahomey. Having agreeably transacted affairs with the Prince we went to the warehouse where they had in confinement four thousand captives in a state of nudity from which they gave me liberty to select one hundred and twenty-five as mine offering to brand them for me, from which I preemptorily [sic] forbid; commenced taking on cargo of negroes [sic], successfully securing on board one hundred and ten.”

According to Foster, Clotilda set sail out of Mobile on March 4, 1860, and arrived on the slave coast of Dahomey in the Bight of Benin on May 15. Anchored offshore, the naked human cargo bought by Foster was ferried through the surf in small boats.

From an 1890 account by Captain Foster:

“Early in the morning, I went on board, and left the first mate on shore to tally them aboard; after securing 75 aboard, we had an alarming surprise when man aloft with glass sang out “Sail ho,” steamer leeward ten miles. I looked and, behold black and white flags, signals of distress, interspersed the coast for fifteen miles, and two steamers hove in sight for purpose of capture.”

“The crew thinking our capture inevitable, refused duty and wanted to take any boats from the vessel and go on shore but could not have landed with our boats owing to the surf. While getting underway two more boats came along side with thirty five more negroes, making in all one hundred and ten; left fifteen on the beach having to leave in haste. All under headway, both steamers changed their course to intercept us, the wind being favourable; in a short time we knew we were outsailing them; then my crew showed their appreciation for not letting them take my boats to go on shore; in four hours were out of sight of land and steamers.”

Clotilda departed Africa on about May 24, 1860 and arrived in Mobile Bay in early July. One girl reportedly died during the six-week brutal crossing.

Purchased for $9,000 in gold as well as merchandise cargo, the imported slaves were worth more than $180,000 in 1860 Alabama.

Articles and books relating the story of Clotilda and her cargo differ widely in some of their information. The date of arrival in Mobile Bay is given as several different days in July 1860 as well as autumn of 1859; The number of slaves varies from 103 up to 160; and the owner of the ship is given as Timothy Meaher, the ship’s captain, William Foster, or is not named.

The snippet from The New York Times of July 11, 1860, citing the arrival as July 9, solidly establishes Clotilda’s arrival in the second week of July. Records from the Mobile U.S. District Court identify the date of arrival in Mobile Bay as July 7, 1860. Captain Foster’s 1890 accounting has the ship anchored off Point of Pines, Grand Bay, Mississippi before July 9. He then writes:

July 9th. went ashore, gave a resident twenty-five dollars for horse and buggy to take me to Mobile. There I got a steam tug to tow schr (schooner) up Spanish river into the Ala. River at “Twelve Mile Island.” I transferred my Slaves to a river steamboat, and sent them up into the canebrake to hide them until further disposal. I then burned my schr. to the water’s edge and sunk her.

July 9th. When anchored off “P. of P.” Miss. The mates and crew did not want me to leave the vessel until they were paid for voyage and said they would kill me if I attempted to take the negroes ashore without their money. Capt. Tim Meaher and party were to have met me there for the purpose of landing negroes, and pay the crew off, and I had made arrangements with the mates and crew, to take the vessel to Tampico and change her name and get clearance for New Orleans – the parties failing to meet me in time, compelled me to come up to Mobile. I hired a tug and went to the vessel to tow her up to Mobile into Spanish River and crew refused to let me have her because I didn’t have time to get the money to pay them. I came back to Mobile and took on board the tug five men and $8,000 dollars, landed [I think] at vessel 9 p.m. Went aboard and settled with them according to my first arrangement in Mobile.

We put the mates and crew on steamer and sent them to Montgomery on their way to the northern states.

Licensed in December 1855, Clotilda’s first record of carrying cargo lists William Foster as Shipper/Owner and Captain Russell as Master of the ship. Foster was to later lament the burning and scuttling of his ship, saying that it was worth far more than the 10 slaves he received as payment. However, without a crew and with the government searching for Clotilda, his choices were limited.

The U.S. government first searched for Clotilda shortly after learning of her illicit voyage, but the endeavor proved fruitless. However, enough information was known for authorities to take legal actions. The Mobile District Court records show that Clotilda entered Mobile Bay with 103 slaves “more or less.”

The cargo was distributed to a number of individuals, including Timothy Meaher, Burns Meaher, James Meaher, John Dabney, Thomas Buford, and Captain William Foster.

On August 7, A. J. Requier, the U.S. attorney for the Southern District of Alabama, informed Judge William G. Jones that “William Foster, master or commander of the Schooner Clotilda … wholly failed to report the arrival of the said schooner Clotilda to the Collector of the said port within the time prescribed by law.” The court wasn’t after Foster for the crime of importing slaves. He hadn’t paid the required fees on his cargo and had not provided information that was required to be inserted in a manifest under oath. He was fined $1000. Without the evidence of the Clotilda to tell the tale, the only charge that could stick was a minor one.

In Mobile, Federal Judge William G. Jones issued orders for Burns Meaher and John Dabner to appear in his court on the second Monday in December. However, the U.S. Marshall didn’t inform them until December 17 and then only verbally. Three days later the Marshall informed the court that the “named negroes” could not be found in his district. Without the Africans, no crime could be found and, on January 10, federal charges against Meaher and Dabney were dismissed.

Also on January 10, 1861, probably because there was money to be collected and his case was easy to prove, an order was issued that the case, The United States vs. William Foster, be continued.

The next day, Alabama seceded from the Union.

Hector Posset, the ambassador of the Republic of Benin and a descendant of the Dahomey royal family visited the site of the recently found Clotilda in 2018. “I am just begging them to forgive us, because we sold them. Our forefathers sold their brothers and sisters. I am not the person to talk to them. No! May their souls rest in peace, perfect peace. They should forgive us. They should,” Posset said, wiping tears from his cheeks. “Qualified people will come and talk to them in due time. I feel so sad.” The qualified people Posset spoke of would be priests of Benin’s traditional religion, Vodun.

Sources used:

- Last American Slave Ship is Discovered in Alabama—National Geographic

- The ‘Clotilda,’ the Last Known Slave Ship to Arrive in the U.S., Is Found—Smithsonian Magazine

- Clotilda (slave ship)—Wikipedia

- Historic Sketches of the South—Roche, Emma Langdon. New York: Knickerbocker Press, 1914.

- Alabama Historians: The Last Known Slave Ship Has Been Found—The New York Times

- The Case for Clotilda—Archaeology

- Last Slaver from U.S. to Africa. A.D. 1860; Transcription of Capt. Foster’s account of the Clotilda voyage and notes accompanying it (with suggestions in [italics]), by Valerie Ellis, Local History and Genealogy, Mobile Public Library—Mobile Public Library Digital Archives

- The Clotilda: A Finding Aid (pdf)—National Archives at Atlanta

- Diouf, Sylviane A. Dreams of Africa in Alabama: the Slave Ship “Clotilda” and the Story of the Last Africans Brought to America. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Dahomey Amazons—Wikipedia

- Cudjoe Kazoola Lewis, the third to last known survivor of the Atlantic slave trade between Africa and the United States, brought illegally to the United States on board the ship Clotilda in 1860—Wikipedia

- Redoshi, second to last known survivor of the Clotilda slave cargo and the U.S. transatlantic slave trade—Wikipedia

- Matilda McCrear, last known living survivor of the U.S. transatlantic slave trade, brought to the United States on the Clotilda—Wikipedia

- Glele, tenth King of the Aja kingdom of Dahomey—Wikipedia

- Ouidah, coastal city of Benin, formerly Kingdom of Dahomey—Wikipedia

- ‘Forgive us, because we sold them,’ says African ambassador on possible slave ship find—Mobile Real-Time News

According to the National Weather Service, “While this storm system was not as strong as the one the week before, strong frontogenetic forcing led to a narrow band of intense snowfall that remained nearly stationary for several hours near a Ponca City to Chelsea to Fayetteville line. Snowfall amounts within this band ranged from 12 to 18 inches in the western part of the band to 18 to 25 inches in the eastern part of the band.”

According to the National Weather Service, “While this storm system was not as strong as the one the week before, strong frontogenetic forcing led to a narrow band of intense snowfall that remained nearly stationary for several hours near a Ponca City to Chelsea to Fayetteville line. Snowfall amounts within this band ranged from 12 to 18 inches in the western part of the band to 18 to 25 inches in the eastern part of the band.”